Basics concepts regarding atomic structure as per cbse class 9

Define the following terms:

(i) Canal rays (ii) Sub atomic particles (iii) Atomic model

Canal Rays: Canal rays are positively charged beam of ions produced in discharge tube. Discovered by E. Goldstein in 1886. Latter these particles were knows as proton.

Sub atomic particles: Electron , proton and neutron are known as subatomic particles. Proton and neutron reside inside the nucleus of the atom and electron revolve around nucleus in discrete orbit.

Atomic Model: Concepts given by scientists on the basis of experiment which explain the structure of atom are known as atomic model . Example J.J Thomson model , Rutherford model and Niel Bohr model of an atom.

J.J. Thomson Model of an atom:

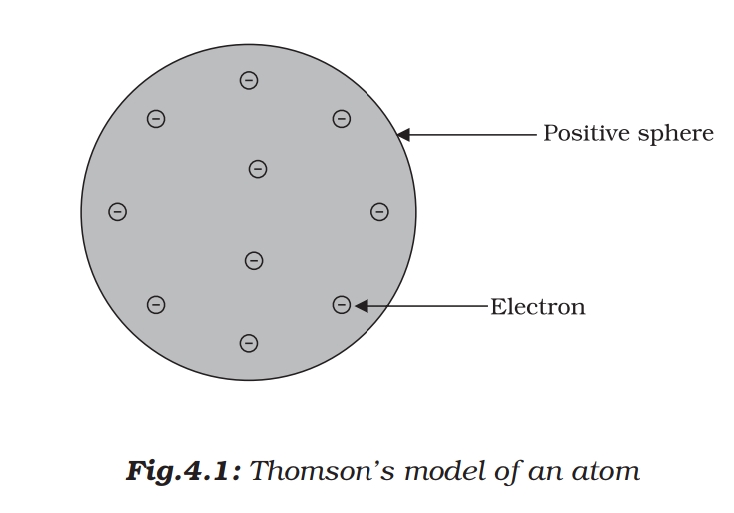

This model is also called plum pudding model. According to this model (i) atom is positively charged sphere in which electrons are embedded. (ii) the magnitude of positive and negative charge are same so atom is electrically neutral.

Limitations of Thomson model of an atom

a. Have not experimental evidences b. Unable to explain nucleus and energy level. do not explain stability of atom.

Rutherford alpha Scattering Experiment:

alpha rays: alpha rays are positively charged ion. It doubly charged Helium nucleus.

Rutherford had taken 1000 atom thick gold foil for his experiment. He chose gold as this metal is highly malleable as he needed thinest sheet for his experiment.

He bombarded alpha rays on gold foil and made following observations:

(i) Most of the alpha rays passes through the gold foil. He concluded most part of atom is empty. (ii) very few rays deflected by some angle. He concluded that deflection must be due to repulsion between postive charges. Thus centre of the atom is positively charged which repel positively charged alpha rays. (iii) One of 12000 rays rebound (a deflection by 180°) this meant for him that approximately whole mass of atom concentrated at the centre of atom. That is further known as nucleus of atom.

Rutherford Model of an atom:

- There is positively charged centre in an atom called nucleus. Nearly all the mass of an atom resides in the nucleus.

- The electrons revolve around the nucleus in well defined orbits.

- The size of nucleus is very small as compared to size of the atom. (Size of Nucleus is about 10^5 times less than radius of atom.)

Drawbacks/ limitation of Rutherford model of the atom:

According to Rutherford electrons revolve in circular orbit. But orbital revolution of of electron is not expected to be stable atom. Any particle moving on circular path undergo acceleration. During acceleration charged particle would radiate energy. Thus revolving electrons would lose energy and finally fall into the nucleus. If this happens then atoms will highly unstable.

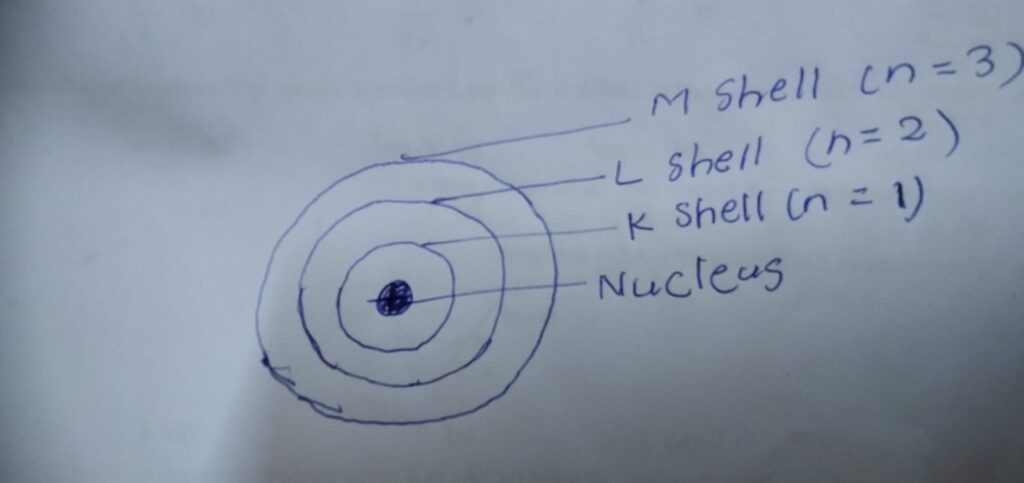

Bohr Model of an atom:

- Only certain special orbits known as discrete orbits of electrons are allowed inside the atom.

- while revolving in discrete orbits the electrons do not radiate energy.

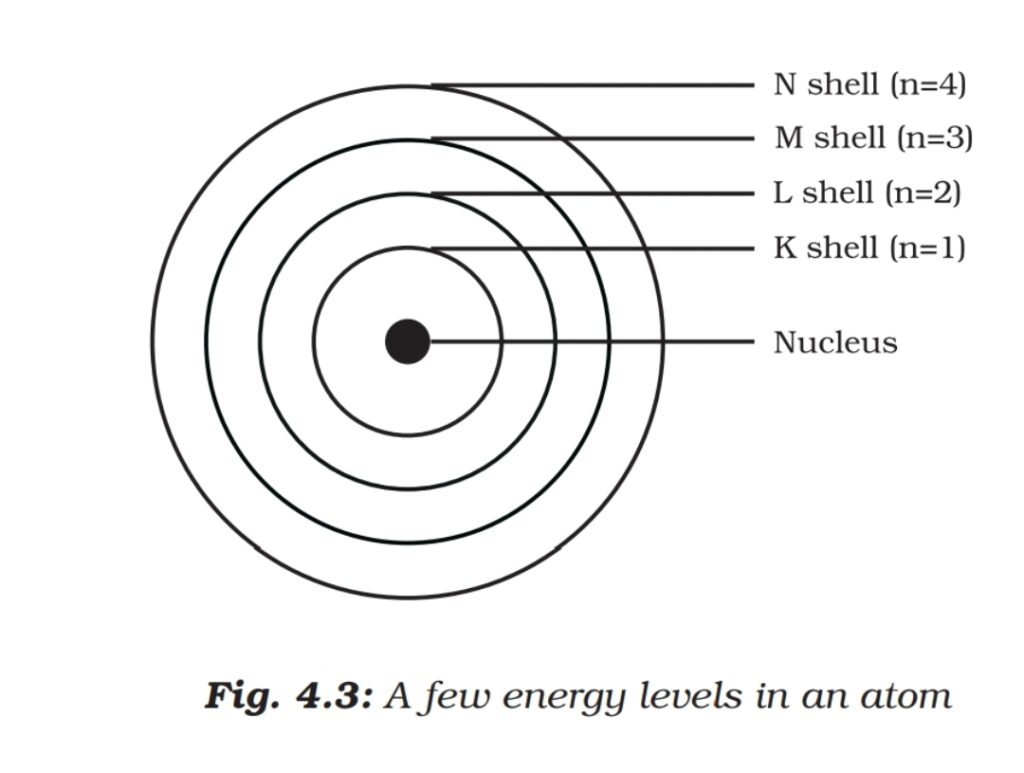

These orbits or shells are called energy levels. The orbits or shells are represented by block letters K, L, M, N,…or by numbers n=1,2,3,4….

Q.) How electrons are distributed in different shells?

Ans: Following rules should be followed while distribution of electrons in given shell:

- The maximum number of electrons present in a shell can be determined by formula 2n^2.

- The maximum number of electrons that can be accommodated in the outermost orbit is 8.

- Electrons are not accommodated in a given she’ll unless the inner shells are filled.

Q.) Define Isotopes and Isobars.

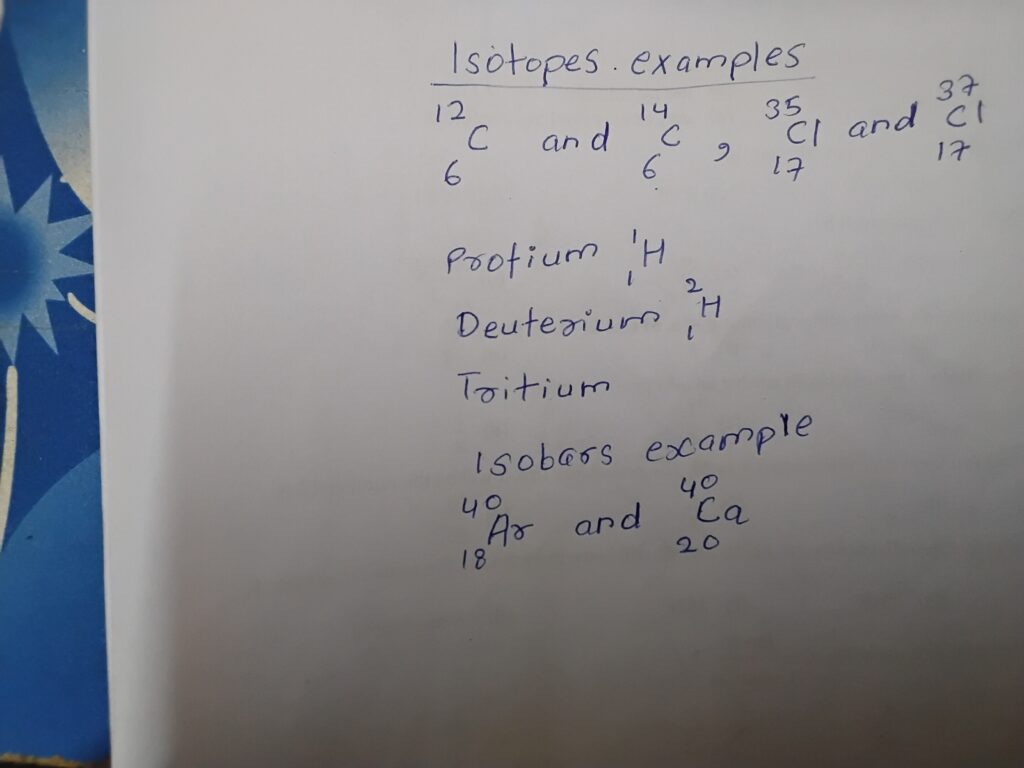

Ans. ISOTOPES: Elements which have same molecular formula but different mass number due to presence of different number of neutrons are called isotope.

ISOBARS: Different Elements which has same mass number and different atomic number are called isobar.

Q. ) What are the uses of isotope?

Ans. Uses of isotopes are as follows:

- Isotope of cobalt are used in the treatment of cancer.

- Isotope of iodine is used in the treatment of goitre.

- Isotope of Uranium is used as fuel in nuclear reactors. ( U-235 and U-238)

Q.) COMPARE the properties of electron proton and neutron.

Ans.

| Particle Properties | e | p | n |

| Location | outside nucleus | inside nucleus | inside nucleus |

| Charge | Negative -1.6×10^-19 Coulomb -1unit | positive 1.6×10^-19 Coulomb +1unit | neutral 0 0 |

| Mass | 9.1×10^-31 kg | 6.67×10^-27 kg | 6.675×10^-27 kg |

| Discovered by | J. J Thomson | E. Goldstein | J Chadwick |

Important note:

- Atomi number (Z)=Number of proton (p)= number of electron (e) in a given neutral atom. That is Z=P=even

- Mass number (A)=number of proton(p)+ number of neutrons. That is A=p+n

- In a given ion Z=p but e=z+(negative charge) or e=Z-positive charge.

- Average atomic mass = sume of product of percentage and mass number of all isotope.

N.C.E.R.T INTEXT QUESTIONS:

Answers:

1. Total charge = total positive charge + total negative charge. According to Thomson total positive and negative charges in an atom are equal but the sign are different so sum of charge is 0. So is neutral as a whole.

2. Proton, he told the centre which is nucleus is positively charge so that it caused reflection of alpha rays.

3.

4. He would not get the same result as other metals are not so malleable. He could not get 1000 atom thick foil.

Answer:1. Three sub atomic particles are electron, proton and neutron.

2. A=p+n

Helium atomic number(Z)=2 so p=Z=2

given A=4 now 2+n=4 so n=4-2=2

………..content is not complete. Updation will be informed.

Advance Reading: Atomic Structure

Atomic structure is a foundational concept in both chemistry and physics, serving as the basis for understanding matter’s composition and the nature of chemical interactions. Every atom consists of three primary subatomic particles: electrons, protons, and neutrons. Electrons are negatively charged particles that orbit the nucleus, while protons are positively charged and found within the nucleus itself. Neutrons, which carry no electrical charge, also reside in the nucleus alongside protons. The interplay between these particles is crucial in determining an atom’s characteristics and behavior.

The arrangement of these subatomic entities plays a significant role in defining the atom’s properties, such as its mass, charge, and reactivity. For instance, the number of protons in the nucleus defines the element itself; this is known as the atomic number. Changes in the number of neutrons result in different isotopes of the same element, influencing physical properties like stability and nuclear reactions. Conversely, the number of electrons determines how an atom interacts chemically with other atoms, influencing molecular formation and bonding.

Understanding atomic structure not only sheds light on the nature of elements but also enhances our comprehension of chemical reactions and material behaviors. The arrangement of electrons in various energy levels around the nucleus impacts how atoms bond with one another, leading to a variety of chemical compounds. Thus, a thorough grasp of atomic structure is paramount for students and professionals in the fields of science, as it lays the groundwork for exploring more complex concepts within chemistry and physics. Ultimately, the study of atomic structure reveals the intricate nature of the universe at its most fundamental level.

Canal Rays: Discovery and Significance

Canal rays, a significant aspect of atomic structure, were discovered by the German physicist Eugen Goldstein in 1886. This discovery came shortly after the recognition of cathode rays, which are streams of electrons emanating from the cathode in a vacuum tube. Unlike cathode rays that are negatively charged, canal rays carried positive charges. This fundamental distinction set the stage for an expanded understanding of atomic theory.

Goldstein’s experiments involved the study of gas discharge tubes, similar to those used in the exploration of cathode rays. When gas is introduced into the tube and subjected to high voltage, Goldstein observed the emission of rays traveling in the opposite direction of the cathode rays. He named these positive rays “canal rays,” as they seemed to emerge from small channels or openings in the cathode. Through these observations, Goldstein highlighted the existence of positively charged particles, which contributed to the idea that atoms consist of both negatively and positively charged components.

The discovery of canal rays was significant for several reasons. First, it provided clear evidence for the existence of positive charge carriers, thus supporting the notion that electrons are not the only fundamental particles in the atom. The identification of these positive particles, later understood to be ions, played a crucial role in developing the contemporary model of atomic structure. Moreover, Goldstein’s findings contributed to the advancement of research on the composition and behavior of matter, helping scientists gain a more comprehensive understanding of the atomic nucleus and its components.

In essence, the discovery of canal rays was instrumental in reshaping atomic theory, illustrating the dynamic interplay between positive and negative charges within an atom. By highlighting the existence of these positive particles, Goldstein paved the way for subsequent research in atomic physics and the eventual development of more sophisticated atomic models.

J.J. Thomson and the Plum Pudding Model

J.J. Thomson, a prominent British physicist, made significant strides in the field of atomic theory in the late 19th century. His most noteworthy contribution was the discovery of the electron in 1897, which fundamentally altered the understanding of atomic structure. Thomson conducted experiments using cathode rays, leading to the conclusion that these rays consisted of small, negatively charged particles, later named electrons. His work provided the first evidence that atoms were not indivisible, as had been previously believed, but rather comprised subatomic particles.

Following his discovery, Thomson developed the plum pudding model of the atom. This model was revolutionary for its time and presented the atom as a spherical entity with a positive charge distributed throughout. The electrons were thought to be embedded within this positively charged “pudding,” resembling plums suspended in a mass of dough. This visualization aimed to explain the neutral nature of atoms despite containing negatively charged particles. Thomson’s model implied that electrons could exist in a uniform positive matrix, suggesting that atomic structure was more complex than mere indivisibility.

The plum pudding model marked a pioneering step in atomic theory, prompting further exploration and refinement. Although later evidence would lead to the rejection of this model in favor of more sophisticated theories, such as Ernest Rutherford’s nuclear model, Thomson’s contributions laid the groundwork for future research into electron behavior and atomic structure. His innovative approach to science exemplified the transition from classical physics to atomic physics, a shift that continues to inform contemporary research in chemistry and physics. By establishing the existence of electrons, Thomson not only redefined the concept of the atom but also ignited curiosity within the scientific community, paving the way for subsequent discoveries in atomic theory.

Ernest Rutherford and the Nuclear Model

Ernest Rutherford, a prominent physicist of the early 20th century, made significant contributions to our understanding of atomic structure through his innovative experiments. His most notable work was the gold foil experiment conducted in 1909, which fundamentally altered the trajectory of atomic theory. Prior to Rutherford’s findings, J.J. Thomson’s plum pudding model was widely accepted, proposing that atoms were composed of a diffuse cloud of positive charge with negatively charged electrons embedded within. However, Rutherford’s experiments revealed a radically different structure.

During the gold foil experiment, Rutherford and his team directed a beam of alpha particles at a thin sheet of gold foil. They expected the particles to pass through with minimal deflection based on the plum pudding model’s premise. Surprisingly, a small fraction of the alpha particles was deflected at large angles, while some even bounced back toward the source. This unexpected outcome indicated that a significant portion of the atom was not empty space, but instead contained a small, dense, positively charged nucleus that repelled the positively charged alpha particles.

Rutherford concluded that the atom consists of a central nucleus surrounded by a cloud of electrons, leading to the formulation of what is now known as the nuclear model of the atom. This model posited that the nucleus is immensely tiny relative to the overall size of the atom, yet it contains most of the mass. Moreover, this finding laid the groundwork for future research into atomic structure, significantly influencing the development of quantum mechanics and the subsequent atomic models proposed by scientists like Niels Bohr.

Overall, Rutherford’s work not only challenged prevailing theories of atomic structure but also established a new framework that remains pertinent in the study of nuclear physics and atomic chemistry. His contributions mark a pivotal moment in the history of science, setting a precedent for further exploration of the fundamental building blocks of matter.

Niels Bohr and the Atom’s Energy Levels

Niels Bohr, a Danish physicist, made significant advancements in our understanding of atomic structure with his revolutionary model proposed in 1913. His approach was particularly notable for introducing the concept of quantized energy levels, which fundamentally changed the way scientists viewed electron behavior within the atom. Prior to Bohr’s contributions, models of atomic structure struggled to explain certain phenomena, especially the discrete spectral lines observed in hydrogen’s emission spectrum.

Bohr’s model posited that electrons exist in specific, quantized orbits or energy levels around the nucleus. Unlike previous models that allowed for a continuous range of possible electron energies, Bohr’s framework dictated that electrons could only occupy certain defined energy states. When an electron transitions between these energy levels, it either absorbs or emits a quantum of energy in the form of light. This explained the distinct spectral lines observed in hydrogen, as each line corresponded to a specific energy transition between two levels.

This quantization of energy levels not only clarified the behavior of hydrogen atoms but also laid the groundwork for future advancements in quantum mechanics. By using the principles of Bohr’s model, scientists could accurately calculate the wavelengths of emitted or absorbed light, validating his theory through experimental observation. Although Bohr’s model had limitations—particularly with more complex atoms—it was instrumental in transitioning the scientific community towards a more robust understanding of atomic structure and electron dynamics.

In essence, Bohr’s introduction of energy levels underscored the importance of quantization in atomic theory, providing a framework within which the complexities of atomic behavior could be better understood. His contributions remain a cornerstone of modern physics and continue to influence the study of atomic and subatomic phenomena.

Subatomic Particles: Electrons, Protons, and Neutrons

Subatomic particles are fundamental constituents of matter, playing pivotal roles in determining the properties and behavior of atoms. Each atom comprises three primary subatomic particles: electrons, protons, and neutrons, each having distinct properties and characteristics that contribute to atomic structure.

Electrons are negatively charged particles that orbit the nucleus of an atom in various energy levels or shells. They possess a negligible mass compared to protons and neutrons, approximately 1/1836 that of a proton. Despite their small mass, electrons significantly influence an atom’s charge and chemical properties due to their ability to form bonds with other atoms. Their distribution around the nucleus determines the atom’s volume and shape, and the arrangement of electrons plays a critical role in how atoms interact and bond with each other.

Protons, on the other hand, are positively charged particles found in the nucleus of an atom. Each proton contributes approximately one atomic mass unit (amu), giving it a considerable effect on the overall mass of the atom. The number of protons in the nucleus defines the atomic number of an element, which ultimately determines the element’s identity. For example, hydrogen has one proton, while carbon has six. Protons are also vital in maintaining the stability of the nucleus, as they contribute to the electromagnetic force that holds electrons in their orbits.

Neutrons, which are electrically neutral, reside alongside protons in the nucleus. They also contribute about one atomic mass unit to the overall mass of the atom. The presence of neutrons affects the stability of the atomic nucleus; variations in the number of neutrons result in isotopes of an element. The forces that hold protons and neutrons together, known as the strong nuclear force, are essential for the integrity of the atomic structure, counteracting the electromagnetic repulsion between positively charged protons. Thus, understanding these subatomic particles is critical for a comprehensive perspective on atomic structure and behavior.

Isotopes: Variations of Elements

Isotopes are defined as variants of a particular chemical element that share the same number of protons but have differing numbers of neutrons. As a result, isotopes of an element possess the same atomic number, which determines the element’s identity, but differ in their atomic mass. This variation in neutron count can significantly influence the stability and properties of the isotopes. For example, carbon has three naturally occurring isotopes: carbon-12, carbon-13, and carbon-14, with the latter being a radioactive isotope commonly used in radiocarbon dating.

The significance of isotopes in the field of chemistry is profound. They play crucial roles not only in understanding chemical processes but also in a range of practical applications. One of the prominent uses of isotopes is in medicine, particularly in diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy. Isotopes such as technetium-99m are widely used in medical imaging to identify conditions within the body due to their ability to emit gamma rays, which can be detected with imaging technology.

Isotopes also have substantial applications in archaeology, specifically in dating ancient artifacts and biological remains. The decay of carbon-14 is fundamental in this context, allowing archaeologists to estimate the age of organic materials up to about 50,000 years old. Furthermore, in the energy sector, isotopes such as uranium-235 are essential for nuclear power generation, as they undergo fission to release significant amounts of energy. This distinguishes isotopes as a vital component not only in scientific research but also in practical applications that impact society.

Isobars: Atoms with Equal Mass

Isobars are fascinating entities in the realm of atomic structure, representing atoms from different elements that share the same atomic mass. The term “isobar” is derived from the Greek words “iso,” meaning equal, and “baros,” meaning weight. Although these atoms display identical masses, they possess differing numbers of protons, which define their unique chemical properties and identity as distinct elements. For instance, carbon-14 and nitrogen-14 are isobars; they both have an atomic mass of 14 but differ in their atomic numbers, which are 6 and 7, respectively.

The phenomenon of isobars arises from the fact that atomic mass is a function of both protons and neutrons present in the nucleus. To maintain the same mass, variations in the quantities of these subatomic particles occur. Typically, when one element undergoes radioactive decay or transformation, it may result in the formation of an isobar. This is commonly witnessed in nuclear reactions, where the number of neutrons can be altered without changing the atomic number, ultimately producing a new isotope or isobar of a different element.

Understanding isobars is crucial in fields such as nuclear chemistry and medicine, particularly in applications involving radioisotopes used for diagnostic imaging or cancer treatment. Isobars may exhibit differences in stability and decay rates, which can impact their utility in medical applications. Moreover, the study of these isotopic forms can provide significant insights into elemental formation and the processes occurring within stars and supernovae. In scientific research, the exploration of isobars aids in elucidating the complexities of atomic interactions and their implications for advanced technologies, including energy production and material science.

Conclusion: The Evolution of Atomic Theory

The evolution of atomic theory represents a remarkable journey through scientific discovery, characterized by crucial advancements and innovative insights that have shaped our understanding of matter. From the early contemplations of ancient philosophers to the rigorous experimentation conducted by pioneering scientists, the path of atomic theory illustrates a continuous quest for knowledge. Initially, concepts surrounding atoms were largely speculative, with Greek philosophers like Democritus introducing the idea of indivisible particles constituting all matter. However, it was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that experimental evidence began to substantiate these early notions.

J.J. Thomson’s discovery of the electron in 1897 marked a significant departure from classical ideas. His introduction of the plum pudding model illustrated a vision of the atom as a sphere of positive charge embedded with negatively charged electrons. This model was revolutionary, yet it was later challenged by Ernest Rutherford’s gold foil experiment in 1909, which revealed the nucleus as a dense, positively charged center surrounded by orbiting electrons. Rutherford’s findings dramatically shifted the scientific paradigm, prompting Niels Bohr to refine the atomic model further in 1913. Bohr introduced quantized energy levels for electrons, providing a more comprehensive explanation of atomic stability and spectral lines.

The contributions of these scientists not only transformed scientific thought regarding atomic structure but also laid the foundation for modern quantum mechanics. Today, ongoing research in atomic and subatomic physics continues to expand our understanding, as scientists delve deeper into the complexities of quarks, leptons, and the fundamental forces governing the universe. This journey through history reveals how each breakthrough builds upon previous knowledge, exemplifying the cumulative nature of scientific inquiry. The theory of the atom remains a cornerstone of modern science and continues to evolve as researchers explore its mysteries.

……………..published by Rahman Sir.